Most UTV winching failures are caused by repeatable mistakes made under load, not weak equipment. When a recovery fails, it happens fast and leaves no margin for correction.

The same errors appear in nearly every unsafe winch recovery: standing in the line of fire, using weak anchors, overloading the winch, shock-loading the line, ignoring heat buildup, mishandling the rope, and losing safe control at the remote.

Fixing these mistakes is what keeps winching predictable instead of dangerous — and that difference matters the moment tension is applied.

Jump To Contents

- UTV Winching Safety: Direct Answers

- What Makes UTV Winching Dangerous? – Safety Fundamentals

- 7 Most Common UTV Winching Mistakes – Quick Overview

- Mistake #1: Standing in the Winch Line of Fire

- Mistake #2: Using the Wrong Winch Anchor Point

- Mistake #3: Overloading a UTV Winch – Rated Capacity vs Real Load

- Mistake #4: Shock Loading the Winch Line

- Mistake #5: Ignoring Winch Duty Cycle and Heat Build-Up

- Mistake #6: Poor Winch Rope Handling and Setup

- Mistake #7: Misusing Wired vs Wireless Winch Remotes

- How Professionals Reduce UTV Winching Risk

- Essential Winching Safety Checklist – Before Every Recovery

- UTV Winching Safety FAQs

- How to Winch Safely When It Matters Most

UTV Winching Safety: Direct Answers

- UTV winching is dangerous because a tensioned winch line stores mechanical energy that can release violently if any component fails.

- In real recoveries, the most serious injuries don’t come from broken winches — they happen when someone is standing inline when a rope or anchor lets go.

- In the winch rope debate, the synthetic winch rope is the winner as it is safer than steel, but it can still recoil and cause injury.

- Winch capacity ratings do not reflect real recovery loads, especially in mud, snow, or uphill pulls.

- Nearly all winch-related injuries are preventable with correct positioning, load management, and controlled technique.

What Makes UTV Winching Dangerous? – Safety Fundamentals

UTV winching is dangerous because it concentrates high mechanical tension, stored energy, and electrical load into a short recovery system, where failure can release force instantly.

Unlike towing, winching stores energy in the rope and anchor system, meaning any breakage results in rapid, uncontrolled force release rather than gradual load transfer.

Notice. UTV winching is not inherently unsafe—the risk comes from how force is generated, stored, and released during recovery, especially in uncontrolled environments such as mud, slopes, or off-camber terrain.

Why do winch recoveries carry inherent risk?

Stored energy in a tensioned line: A winch rope—synthetic or steel—stores elastic energy as load increases. If the rope, anchor, or mounting point fails, the energy is released instantly along the line of pull, creating a snapback zone that can cause severe injury.

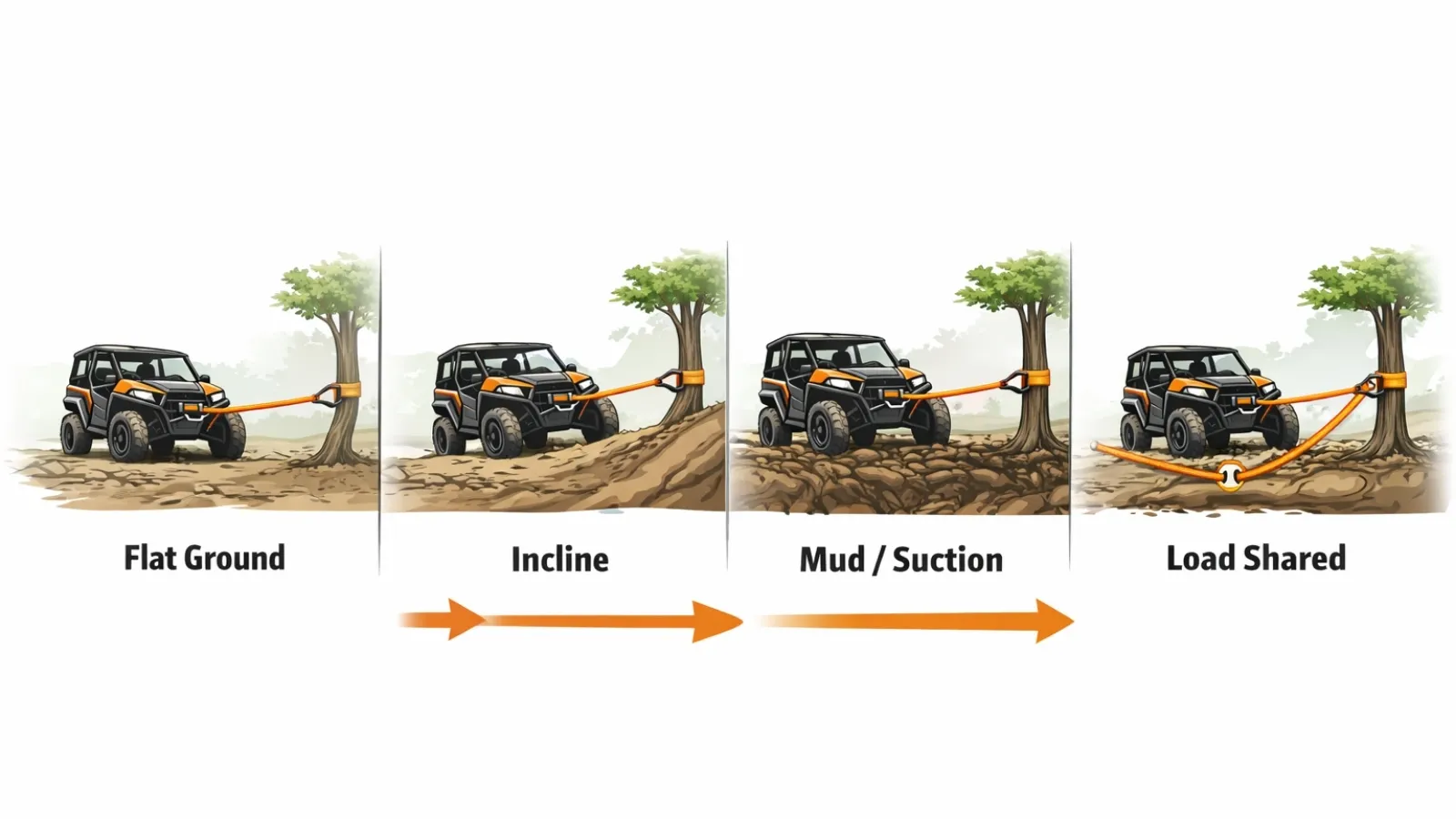

Unpredictable recovery loads: Real-world resistance factors such as mud suction, incline angle, rolling resistance, and cargo weight routinely multiply recovery force beyond static vehicle weight. This is why rated winch capacity often understates actual stress.

Human proximity to the recovery system: Winch operation places operators closer to the load path than most strap or tow recoveries. Standing near the fairlead, anchor, or rope path significantly increases the risk of injury if failure occurs.

Electrical and thermal stress during sustained pulls: UTV winches draw high current from limited electrical systems. Voltage drop, heat buildup, or stalled motors can abruptly change line behavior, increasing the likelihood of operator error under pressure.

Once you view winching as stored force rather than pulling power, your decisions change immediately. Nearly every winching injury or failure results from ignoring one of these core principles, not from equipment defects.

7 Most Common UTV Winching Mistakes – Quick Overview

Most UTV winching accidents follow repeatable error patterns where small technique mistakes escalate under load.

The mistakes below represent the most frequent failure points observed in real-world UTV recoveries and are consistently cited in injury reports, training debriefs, and professional recovery instruction.

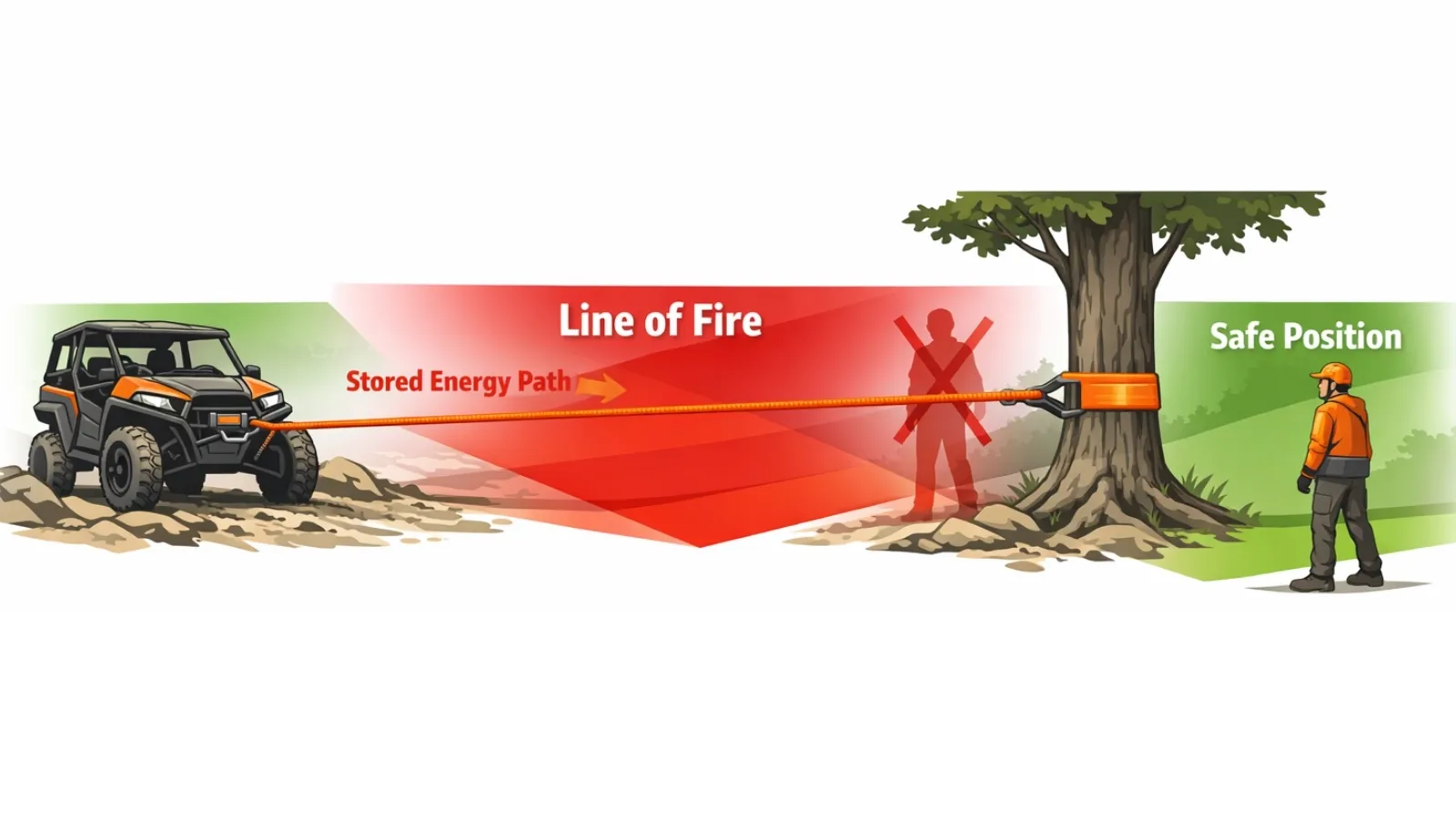

Standing in the line of fire: It means positioning yourself or bystanders directly along the path of a tensioned winch rope. If any component fails, stored energy is released along this path, creating severe snapback risk.

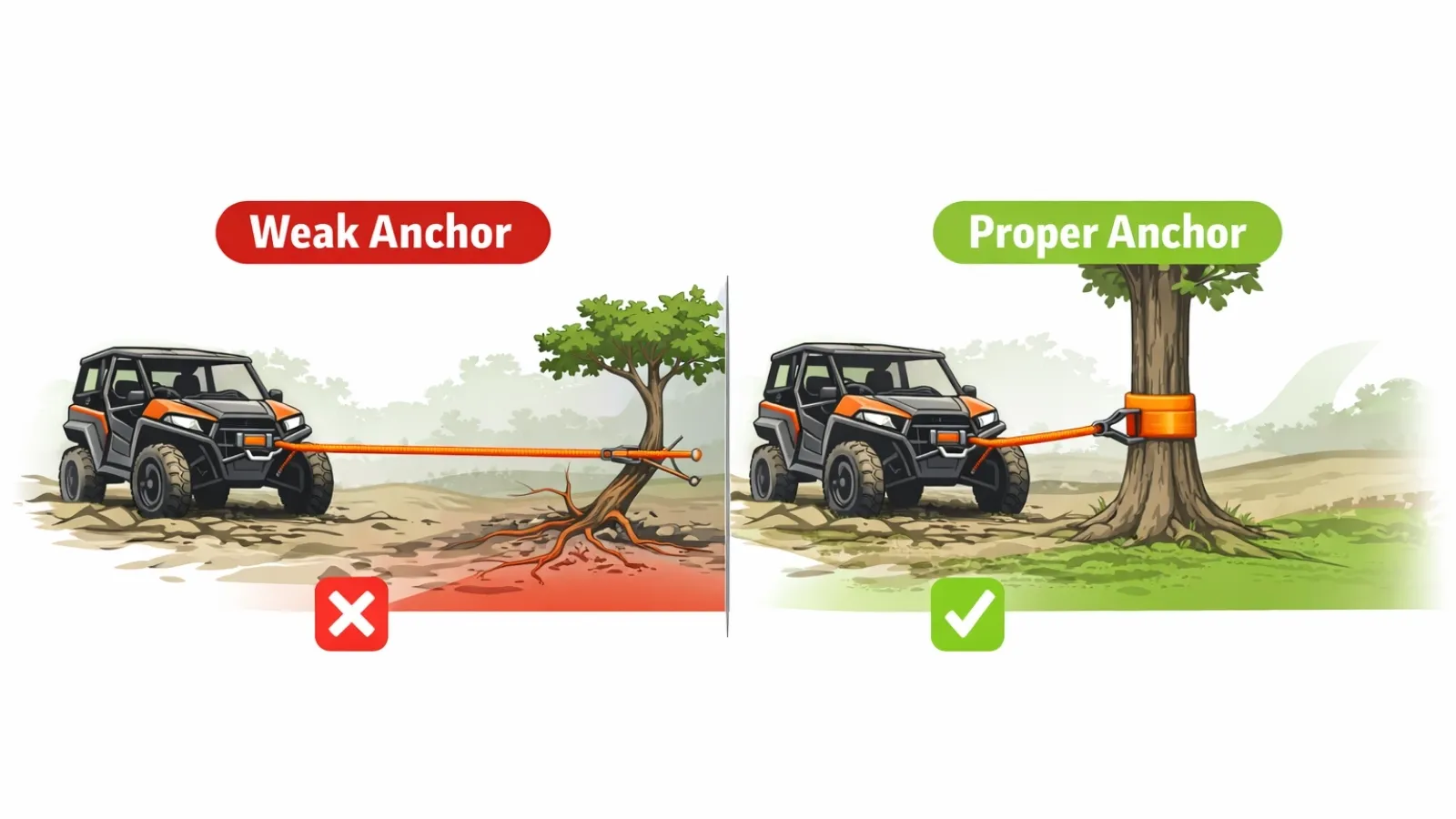

Using a weak or poorly chosen anchor point: The anchor fails, releasing the full recovery load instantly. Improvised or visually solid anchors often lack the structural strength required to handle multiplied recovery forces.

Overloading the winch: Winch overload occurs when real recovery resistance exceeds safe operating capacity—even if the winch is rated above vehicle weight. Overload increases electrical strain, heat buildup, and component failure risk.

Shock loading the winch line: occurs when tension is applied abruptly rather than gradually. Jerking force spikes exceed design limits and damage ropes, mounts, and anchors.

Ignoring duty cycle and overheating: Continuous pulling without rest overheats the winch motor and electrical system. Heat reduces efficiency, increases stall risk, and encourages unsafe operator decisions.

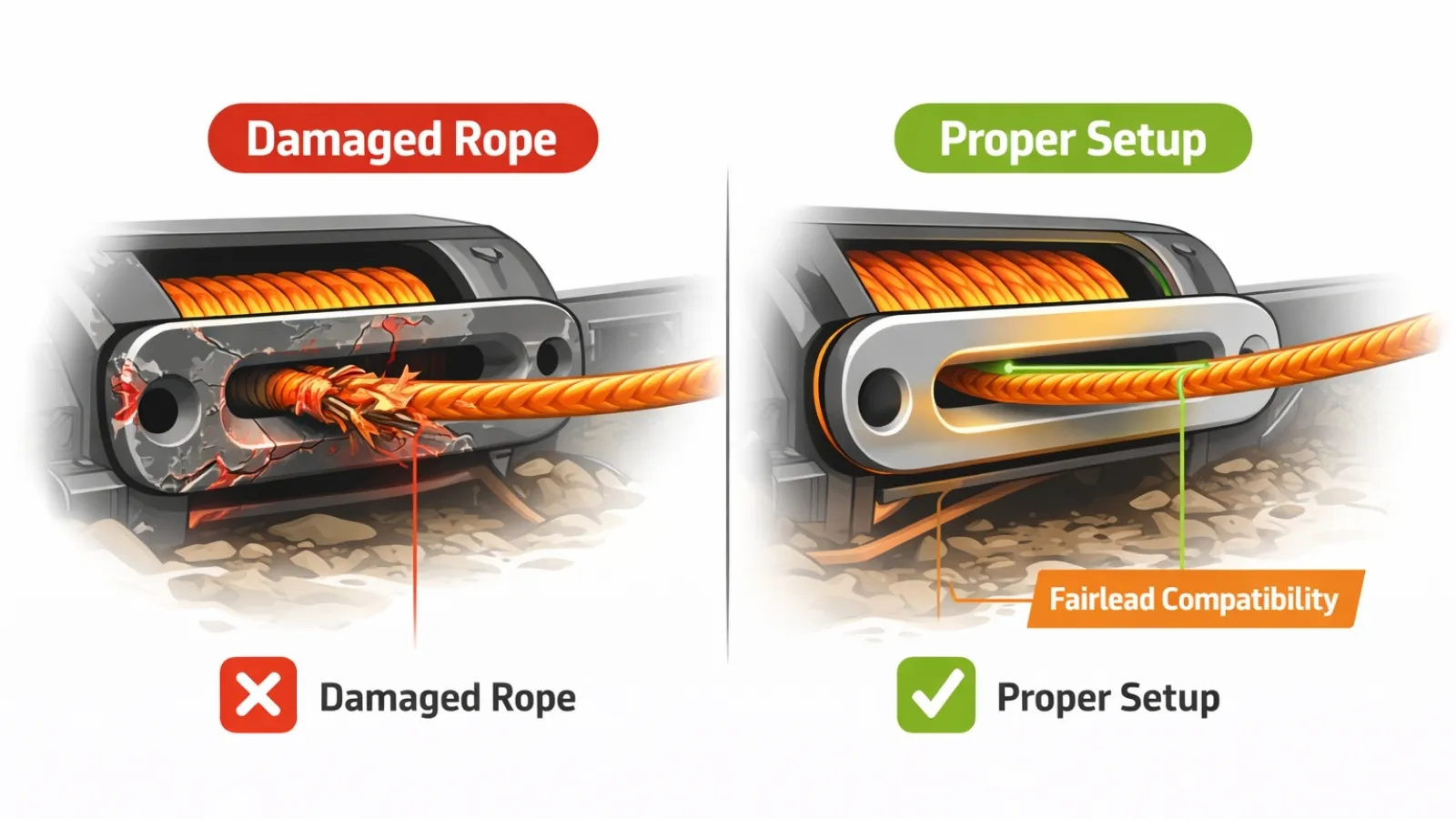

Poor rope handling and setup: Improper spooling, abrasion exposure, fairlead mismatch, and skipped inspections weaken the rope before recovery begins, leading to sudden under-load failure.

Misusing wired or wireless winch remotes: Remote misuse places operators too close to the recovery system or causes control loss at critical moments, increasing exposure to snapback and system-failure zones. It’s a strange habit, but people still walk toward a loaded winch when control gets uncertain — exactly when they should be creating distance.

Each of these mistakes is mechanically preventable through technique, not stronger equipment. The following sections explain why each error is dangerous and how experienced operators mitigate risk before failure.

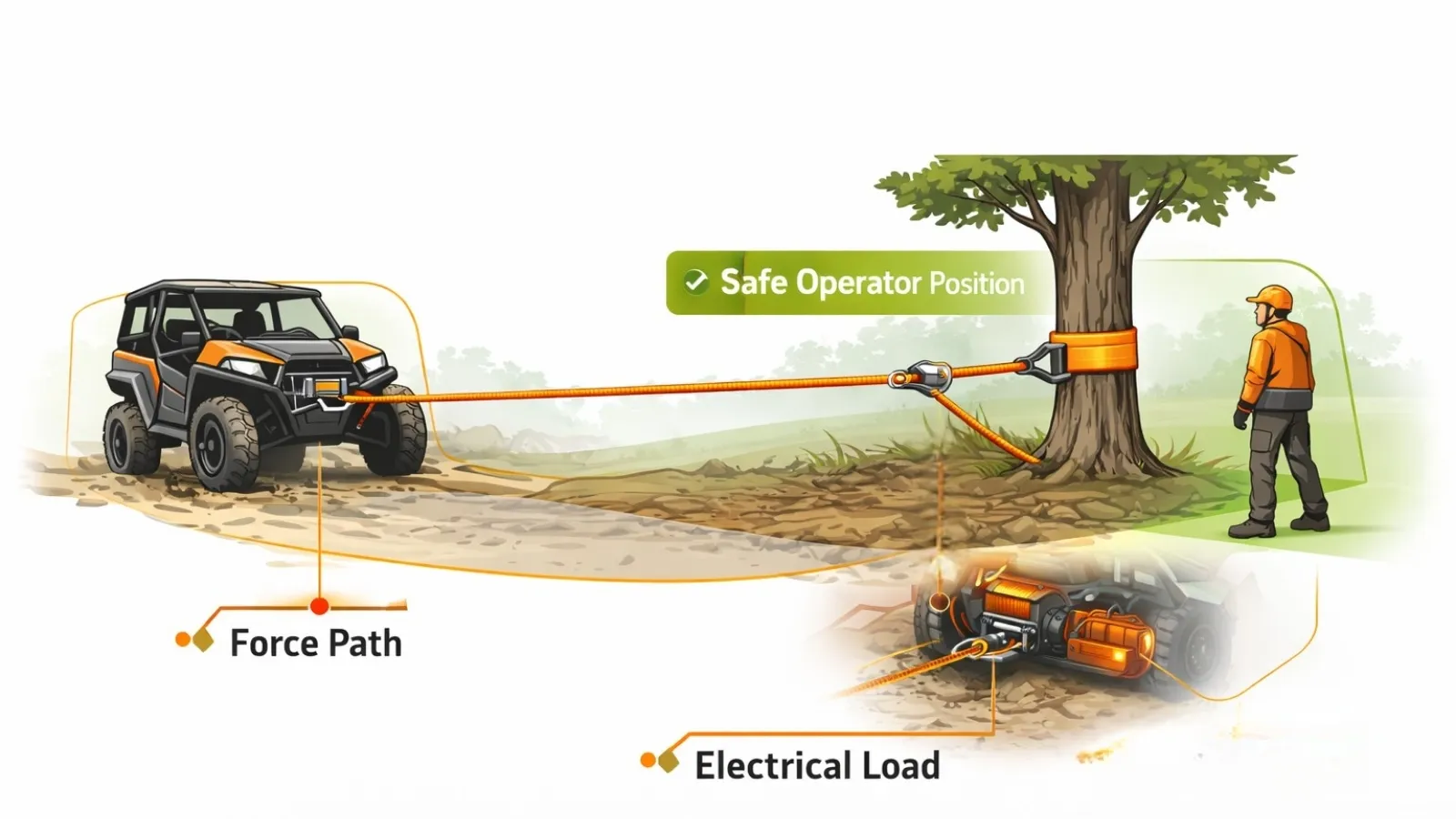

Mistake #1: Standing in the Winch Line of Fire

If there’s one mistake that causes the worst injuries in winch recoveries, it’s standing in the line of fire. When a winch line fails, it doesn’t ‘whip’ gradually — it snaps instantly. People get hurt because they’re standing where everything is already loaded and moving. This is how hands, faces, and legs end up in the injury reports — not from distance, but from alignment.

Why is the line of fire dangerous?

Stored energy releases instantly: Once the line is tight, you’re no longer dealing with movement — you’re dealing with stored force. When something lets go, there’s no warning and no time to react.

Direction matters more than distance: Standing several feet away but inline with the rope is more dangerous than standing farther away at an angle.

Synthetic rope is safer—but not safe: Synthetic rope reduces recoil energy compared to steel cable, but still snaps back under load and can cause serious injury.

How professionals reduce exposure?

Stand off-axis: Operators position themselves to the side of the rope path, never in front of the winch or anchor.

Clear the snapback zone: All bystanders are moved well outside the recovery force path before tension is applied.

Use energy dampers: Winch line dampers or recovery blankets reduce recoil severity if failure occurs.

Operate remotely when possible: Wireless remotes allow control from outside the line of fire while maintaining visibility.

Line-of-fire discipline is considered non-negotiable in professional recovery. Correct positioning alone eliminates one of the most severe mechanisms of winching injury.

Mistake #2: Using the Wrong Winch Anchor Point

Choosing the wrong anchor point means attaching the winch line to an object that cannot safely withstand multiplied recovery loads. When that anchor fails, it releases the full stored energy of the recovery system instantly—often more violently than rope or winch failure.

Anchor failure is especially dangerous because it is frequently unexpected and occurs under peak tension.

Why is anchor failure high-risk?

Anchor failure releases total system energy: Unlike gradual winch stalls, anchor breakage causes immediate force release along the rope path, creating severe snapback risk. This is the failure that puts hardware, rope, and people in motion simultaneously.

Visual strength is misleading: This is especially common on muddy trails and forest edges, where trees look solid but are sitting in saturated soil that can’t hold recovery load.

Recovery forces multiply quickly: Mud suction, incline angle, rolling resistance, and vehicle load can double or triple anchor stress compared to static vehicle weight.

How do professionals choose safer anchors?

Prioritize structural strength: Use large, healthy trees with deep root systems or purpose-built ground anchors when available.

Distribute load correctly: Tree saver straps spread force and prevent cutting or uprooting the anchor.

Control the pull geometry: Align the winch pull to avoid side-loading the anchor, which increases the risk of failure.

Reduce force early: Use snatch blocks to lower the winch and anchor load before maximum tension is reached.

If the anchor isn’t right, everything downstream is already compromised — no amount of winch control can fix that. A strong winch attached to a weak anchor is not a recovery—it is a delayed failure.

Mistake #3: Overloading a UTV Winch – Rated Capacity vs Real Load

Overloading a winch occurs when real recovery resistance exceeds safe operating load, even if the winch’s rated capacity appears sufficient.

Winch ratings are measured under ideal conditions; real-world recoveries routinely exceed those assumptions through terrain resistance and technique errors.

Rated pull is a marketing number. Safe recovery capacity is a system calculation.

Why is winch capacity commonly misunderstood?

Ratings apply only to the first drum layer: As rope accumulates on the drum, effective pulling power decreases significantly, reducing available force under load.

Recovery load exceeds vehicle weight: Mud suction, incline angle, rolling resistance, and added cargo can easily double the force required to extract a stuck UTV.

Electrical systems are a limiting factor: as load increases, current draw rises sharply. Small UTV batteries and stators struggle to supply sustained amperage, leading to voltage drop, heat buildup, and stalled pulls.

On most UTVs, that means small batteries, limited stator output, and very little margin for sustained high-amp pulls.

How do professionals avoid winch overload?

Built-in capacity margin: Winch size is chosen based on worst-case recovery conditions, not dry vehicle weight.

Use mechanical advantage early: Snatch blocks reduce winch load, electrical strain, and heat generation before overload occurs. When recovery resistance climbs, mechanical advantage is the difference between a controlled pull and a system pushed toward failure.

Monitor line speed and sound: Sharp drops in line speed or motor tone indicate excessive load and require reassessment.

Treat stalling as a stop signal: A stalled winch is a warning, not a challenge to apply more force.

When resistance spikes and progress stops, forcing the pull is how mounts bend, solenoids cook, and anchors fail. Overload prevention preserves equipment, protects electrical systems, and stops rushed decisions that compromise safety.

Understanding why real recovery loads exceed rated winch capacity is foundational to safe winching. This same load-multiplication logic is used when evaluating winch size, rope type, and accessory selection, which are addressed in the broader UTV winch system overview.

Mistake #4: Shock Loading the Winch Line

Shock loading is the sudden application of force to a winch line instead of gradual tension buildup. This happens when impatience meets tension — and it breaks gear faster than almost anything else.

Winching systems are designed for steady loads, not impact forces. That’s why sudden force spikes can exceed component ratings even when all equipment is properly sized.

Shock loading is one of the fastest ways to break ropes, damage mounts, and fail anchors.

How does shock loading occur?

Combining throttle with winching: Applying throttle while the winch line is tight creates rapid force spikes as the vehicle lunges forward.

Jerky winch control: Rapid on–off operation prevents tension stabilization and repeatedly shocks the rope and hardware.

Slack followed by sudden tension: Allowing slack to develop and then reapplying load causes the rope to snap tight abruptly.

Why is shock loading dangerous?

Force spikes exceed rated capacity: Momentary loads during shock events can surpass winch, rope, and mounting limits.

Accelerated equipment fatigue: Repeated shock weakens rope fibers, deforms hardware, and shortens component lifespan.

Increased electrical and thermal stress: Sudden load spikes draw extreme current, increasing heat and stall risk.

How do professionals prevent shock loading?

Maintain steady line speed: Winch smoothly with continuous, controlled input.

Limit vehicle assistance: Keep the vehicle in neutral unless controlled assistance is required and coordinated.

Eliminate slack: Manage rope tension deliberately to prevent snap-tight events.

Reduce resistance mechanically: Use snatch blocks when resistance is high, rather than forcing the system.

Controlled tension is the foundation of safe winching. Smooth pulls provide time to stop before damage or injury occurs.

Mistake #5: Ignoring Winch Duty Cycle and Heat Build-Up

Ignoring duty cycle means operating a winch beyond its designed intermittent run time, allowing heat to accumulate faster than it can dissipate.

Excessive heat reduces winch efficiency, increases the risk of electrical failure, and makes recovery behavior unpredictable.

Most UTV winches rely on the operator—not internal protection—to manage thermal limits.

Why heat build rapidly during winching?

High current draw under load: As resistance increases, amperage rises sharply, accelerating the heating of the motor and solenoid.

Extended run time at slow line speed: Heavy pulls take longer, allowing heat to accumulate even when the winch appears to be functioning normally.

Poor cooling conditions: Mud, water, snow, and restricted airflow trap heat around the motor and electrical components.

Warning signs of thermal overload

Sudden loss of line speed: Reduced pulling speed without added resistance signals overheating.

Intermittent or stalled operation: Winch stops responding despite continued input.

Excessive component heat: Motor, solenoid, or cables feel unusually hot to the touch.

These are safety warnings, not performance issues.

How do professionals manage the duty cycle?

Winch in short intervals: Apply tension in controlled bursts rather than continuous pulls.

Allow cooling pauses: Stop winching when performance drops and let the system recover.

Reduce load mechanically: Use snatch blocks to lower amperage draw and heat generation.

Reassess instead of forcing progress: Unexpected performance changes trigger reevaluation, not increased effort.

Heat management preserves electrical systems, prevents stalls under load, and keeps recoveries predictable and controlled. An in-depth breakdown of the role the winch duty cycle plays in recovery is crucial to fully grasp that point.

Mistake #6: Poor Winch Rope Handling and Setup

Poor rope handling refers to improper spooling, inspection, or protection of the winch line that weakens it before recovery begins. Most rope failures are not sudden—they are the result of accumulated damage introduced during setup and handling.

By the time load is applied, failure conditions may already exist.

Uneven or loose drum spooling: Rope spooled without tension can bury under load, creating pinch points that damage fibers and reduce pulling efficiency.

Abrasion and edge contact: Synthetic rope is highly susceptible to abrasion and edge contact. Contact with rocks, sharp edges, or damaged fairleads weakens the rope at hard-to-see locations.

Mismatched rope and fairlead: Incorrect rope–fairlead combinations accelerate wear and increase failure risk under tension.

Skipped pre-recovery inspection: Cuts, frays, glazing, or flattened sections often go unnoticed until maximum load is applied.

How do professionals prepare the winch line?

Spool under light tension: Even layering prevents rope damage and ensures a consistent pulling force.

Inspect the full rope length: Check for abrasion, heat damage, or deformation before serious recoveries.

Protect the line path: Use abrasion sleeves or edge protection when pulling over rocks or ledges.

Match hardware correctly: Ensure rope type and fairlead condition are compatible and replace worn components promptly.

Rope handling issues rarely exist in isolation. Rope material, fairlead compatibility, mounting geometry, and accessory use all influence how damage develops over time. These factors are part of the complete winch setup considerations covered at the system level. If any part of that setup is weak, it will show up under load.

Mistake #7: Misusing Wired vs Wireless Winch Remotes

Remote misuse occurs when winch controls place the operator too close to the recovery system or create a loss of control during active pulls.

Winch remotes are safety devices; incorrect use increases exposure to snapback and to system failure zones.

Most remote-related incidents stem from positioning and redundancy failures—not electronics.

Where remote misuse creates risk?

Limited stand-off distance with wired remotes: Short cables encourage operators to stand near the winch line, fairlead, or anchor during high-tension pulls.

Unverified wireless control: Wireless remotes can lose signal or power. Failure during a pull often causes operators to move toward the vehicle under load.

Reduced system visibility: Operating without a clear view of the rope path, anchor, and vehicle movement delays reaction to early failure signs.

How do professionals use remotes safely?

Maximize distance from the force path: Wireless remotes are preferred to allow off-axis positioning during solo recoveries. They’re not perfect — batteries die and signals drop — which is why experienced operators test them before load and keep a wired backup accessible.

Maintain redundancy: Wired remotes are kept as tested backups, not primary control methods.

Pre-test wireless systems: Remote functionality is verified before recovery begins—not during load.

Prioritize visibility over convenience: Operators position themselves where the entire system is visible, not just the stuck vehicle.

The safest remote setup balances distance, visibility, and redundancy. Control without visibility—or visibility without distance—creates unnecessary risk.

How Professionals Reduce UTV Winching Risk

Professional winching focuses on controlling energy rather than maximizing force. And experienced operators reduce risk by managing load paths, heat, positioning, and decision timing—long before equipment strength becomes a factor.

Safe recoveries are methodical, predictable, and deliberately slow.

Core principles professionals follow

Plan before applying tension: Anchor selection, line path, operator position, and escape direction are established before the winch is engaged.

Build tension gradually: Slow, steady pulls allow early detection of anchor movement, rope issues, or electrical strain.

Reduce force mechanically, not electrically: Snatch blocks are used early to lower winch load, electrical draw, and heat generation.

Maintain safe stand-off distance: Operators stay outside the line of fire while maintaining full visibility of the recovery system.

Stop immediately when conditions change: Unexpected noise, sudden speed changes, or anchor shift trigger an immediate halt—not continued pulling.

Professional recoveries prioritize predictability over speed. This approach minimizes injury risk, extends equipment life, and prevents small problems from escalating under load.

Essential Winching Safety Checklist – Before Every Recovery

A pre-recovery safety checklist prevents most winching injuries by identifying failure points before tension is applied.

Experienced operators use short, repeatable checks to eliminate avoidable risks rather than reacting under load.

This checklist is designed for fast scanning and consistent execution.

Pre-winching safety checklist

Winch rope inspected: Check the full rope length for cuts, frays, glazing, flattening, or abrasion. Damaged rope is replaced before recovery begins.

Anchor verified: Confirm the anchor is structurally sound, properly protected with a tree saver or strap, and aligned to minimize side-loading.

Line path cleared: Ensure the rope is not contacting sharp edges, rocks, or hardware. Use abrasion protection where needed.

Line damper installed: Place a winch damper or recovery blanket over the rope to absorb energy if failure occurs.

Bystanders cleared: Move all people outside the snapback and line-of-fire zones before applying tension.

Electrical system ready: Engine running when appropriate, battery healthy, and wiring secured away from moving or heated components.

Recovery plan confirmed: All participants understand the pull direction, signals, and stop conditions before winching begins.

Running this checklist takes less than a minute and eliminates the most common causes of winch-related injuries and equipment damage.

UTV Winching Safety FAQs

Is winching with a UTV dangerous?

Yes. UTV winching is dangerous because a tensioned winch line stores mechanical energy that can release violently if the rope, anchor, or mounting point fails. Proper positioning and controlled technique significantly reduce this risk.

Can a synthetic winch rope snap back and cause injury?

Yes. Synthetic winch rope stores less energy than steel cable, but it can still recoil under load. Standing in the line of fire remains dangerous regardless of rope type.

Should you use throttle while winching a UTV?

No. Applying throttle during winching can create shock loads that exceed the winch, rope, and anchor ratings. Controlled winching should be done with steady line tension and minimal vehicle input.

How far should you stand from a winch line?

You should stand well outside the direct path of the winch line, ideally at an angle where you can see the entire recovery system while remaining outside the snapback zone.

When should you use a snatch block for winching?

A snatch block should be used when recovery resistance is high, anchor strength is questionable, or additional control and load reduction are needed.

How to Winch Safely When It Matters Most

Most UTV winching injuries and failures aren’t random. They happen when force is applied without controlling where it goes, how it’s managed, and who is exposed to it.

Safe winching comes down to discipline under load: staying out of the line of fire, choosing anchors that can actually hold, managing real recovery forces, avoiding shock loads, controlling heat, and handling rope and remotes with intent. These habits don’t slow recoveries down — they keep them predictable.

When winching is treated as a controlled energy system rather than a pulling tool, equipment lasts longer, recoveries remain stable, and injuries stop. That margin is built before tension is applied — and it’s what separates clean recoveries from preventable failures.

Those same forces are also what determine whether a winch is actually capable of safe recovery in real terrain, where line speed, electrical strain, rope behavior, and system setup matter more than rating labels.

Continue Exploring Related Topics:

- Finding the best value UTV winch

- Key differences between ATV and UTV winches

- How winch brands affect reliability

ATVNotes is an off-road resource focused on ATV and UTV winching, recovery systems, safety gear, tires, batteries, and essential off-road equipment. Content is produced by the ATVNotes Expert Team and written from the perspective of a practical off-road recovery advisor, emphasizing real-world performance, system compatibility, and safety-first practices across trail riding, utility use, and off-road exploration.